-

Prasanto K Roy

29th Mar 2015

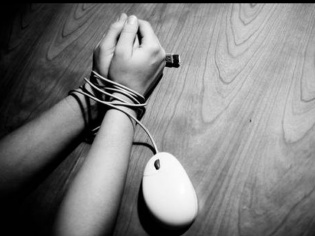

India’s highest court has struck down a law that made posting offensive comments a crime punishable by a prison term of up to three years.

Section 66A was sweeping and draconian, say free speech campaigners, and was repeatedly abused across the country.

What was 66A and why was it bad?

Inserted in 2009 into India’s Information Technology Act of 2000, section 66A allowed anyone to be arrested for posting any ‘offensive’ message on social media or sending it via email, and jailed for up to three years. 66A was sweeping and draconian, and was repeatedly abused across the country. It criminalized 'offense' and 'annoyance', leaving it to police officials and others to interpret what those meant. Any message could 'annoy' someone. 66A was repeatedly abused by politicians taking offence at posts about them.Who abused it, and how?

This month, a 12th class student was arrested and jailed in Uttar Pradesh for two days for a Facebook post about minister Azam Khan. Back in 2012, two girls were arrested in Mumbai for a Facebook post criticising the shut-down of Bombay after Bal Thackeray's death (one of them had just 'liked' the post). In the same year a Puducherry businessman was arrested for tweeting that Congress politician Karti Chidambaram had amassed much wealth. A professor in Kolkata’s Jadavpur University was arrested for forwarding a cartoon on chief minister Mamata Banerjee.Who finally killed 66A?

Section 66A was challenged in 2012 by a young law student, Shreya Singhal, then 21. She filed a public-interest litigation in the Supreme Court, shortly after the arrest of the two girls in Mumbai for their Facebook post. Nearly a dozen other petitions followed.Who fought 66A in the Supreme Court?

Petitioner Shreya Singhal’s case was argued by India’s former attorney general Soli Sorabjee. Others also filed petitions about 66A and related laws in the same act: these petitions were grouped together and included by the supreme court in its final order of March 24, striking down 66A. Petitioners included the consumer review portal Mouthshut.com, NGO Common Cause represented by lawyer Prashant Bhushan, NGO People’s Union for Civil Liberties represented by Karuna Nundy, Apar Gupta, and others.Who supported and defended 66A in court?

In the first two years since the case was filed in court, it was defended by the UPA government’s representatives. 66A and related laws in 2009 were drafted during the UPA regime, and it was also defended in public and media by Congress politicians, especially then law minister Kapil Sibal. The BJP’s Arun Jaitley had attacked the law in the Rajya Sabha, after it was reported that the government had blocked nearly 300 websites. Once in power in 2014, however, the BJP, swung around to defending 66A in the court, its government represented by additional solicitor general Tushar Mehta. "The same Arun Jaitley who said 66A was like an online emergency…his party has been defending it now as a 'necessary legislation'," said Congress MP Shashi Tharoor.Was 66A completely killed?

Yes, it was completely struck down. The judgement, read out by Justice RF Nariman, said that section 66A was unconstitutional and directly affected the public's right to know. "We have no hesitation in striking it down in its entirety," he said. The court order noted that section 66A violates an article of the Indian constitution that guarantees freedom of speech and expression.If it was a bad law, why did it take so long to kill it?

One reason is the slow pace of the judiciary in India, where many cases take decades, and three years is considered unusually fast. Even the specially fast-tracked Nirbhaya rape case took over a year, and appeals are still on in its third year. But the bigger reason was that the government of the day, first the Congress-led UPA, then the BJP, aggressively defended 66A in the supreme court. It appeared that any government in power wanted to retain 66A, unnecessarily prolonging the battle.So why are free-speech campaigners still unhappy?

The petitioners had challenged not just 66A but other provisions introduced in the 2009 amendment, notably 69A, which allows the blocking of websites. Hundreds of websites and web pages have been blocked under 69A, including, in 2013, a government website. One petitioner, Mouthshut, has received over 800 ‘takedown’ orders for the consumer complaints posted on its website.What is section 69A?

Section 69A allows the government to block online content that "threatens the security of the state" or fulfills other conditions. The supreme court order of March 24 upheld the section, noting that 69A is a "narrowly drawn provision with several safeguards". However, it clarified that the blocking order must be specific and clear and should come from the government, or from a court.What now? Is free speech assured? Can anyone say anything?

Post 66A, arbitrary arrests for 'offensive statements' should reduce, and online free speech will be easier. However, there are provisions in other laws for moderating hate speech. For instance, section 295A of the Indian Penal Code provides for a similar jail term for "acts intended to outrage religious feelings". However, such provisions are less vague and arbitrary, and thus less prone to misuse, than 66A was. Also, 69A remains, which allows the blocking of specific web sites or pages with a government or court order.

Prasanto K Roy (Twitter: @prasanto) is head of media services at Trivone Digital Services.

66A FAQ: Why the Campaigners Are Still Unhappy | TechTree.com

66A FAQ: Why the Campaigners Are Still Unhappy

Ten questions on India’s controversial law that was struck down this week.

News Corner

- DRIFE Begins Operations in Namma Bengaluru

- Sevenaire launches ‘NEPTUNE’ – 24W Portable Speaker with RGB LED Lights

- Inbase launches ‘Urban Q1 Pro’ TWS Earbuds with Smart Touch control in India

- Airtel announces Rs 6000 cashback on purchase of smartphones from leading brands

- 78% of Indians are saving to spend during the festive season and 72% will splurge on gadgets & electronics

- 5 Tips For Buying A TV This Festive Season

- Facebook launches its largest creator education program in India

- 5 educational tech toys for young and aspiring engineers

- Mid-range smartphones emerge as customer favourites this festive season, reveals Amazon survey

- COLORFUL Launches Onebot M24A1 AIO PC for Professionals

TECHTREE